Money, as ubiquitous as it is, few really understand it, you might consider the U.S. Dollar to be omnipotent, the safest and most globally accepted currency, but around 30% of surveyed respondents incorrectly believe it is still backed by gold (it hasn’t been since 1971). Money, like USD, is now ‘fiat’ (Latin for ‘it shall be’), no longer backed by anything but a governments word and fiscal discipline.

But the U.S. could never default on its debt, right? That’s only for countries like Argentina and Venezuela? Nope, the U.S. defaulted in 1971, 1968 and 1933. Each default allowed for the creation of more dollars by reducing or removing the requirement to back these new dollars with gold.

It important to understand the fiat system is an improvement on previous systems but is still flawed and will continue to evolve, Winston Churchill used to say ‘democracy is the worst form of government, with the exception of all other forms of government’, I’d say the same of fiat money.

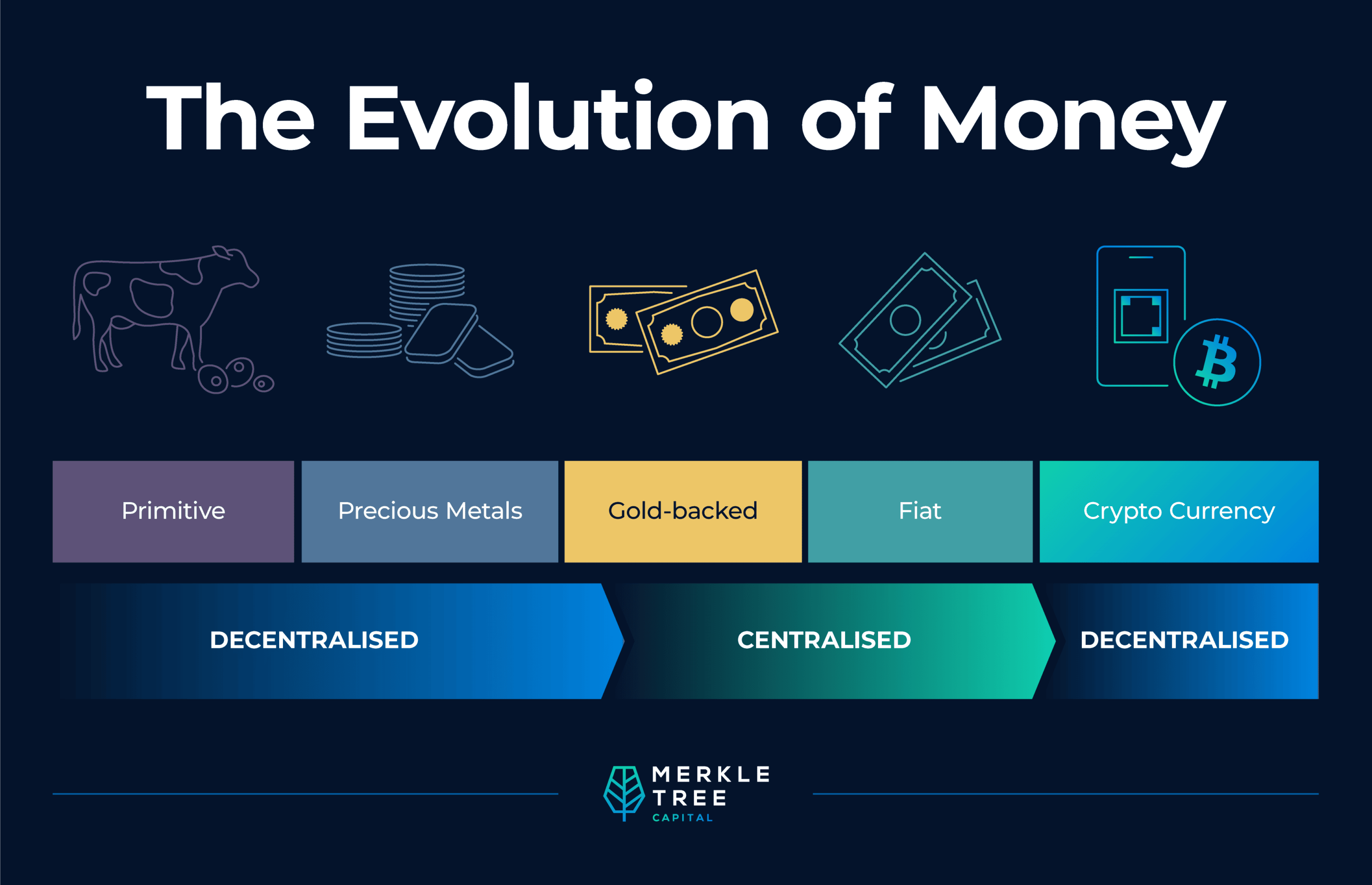

At Merkle Tree Capital we believe that Bitcoin is simply the next iteration in the human race’s long history with money. Further, we believe that this long process of the evolution of money has seen every new stage contested bitterly by vested interests, and the human tendency to inertia and unwillingness to change.

But we argue that the excesses in, and debasement of, the world’s “fiat” money system so far in the 21st Century have made a new iteration not only inevitable, but desirable.

We believe that the discussion comes down to a simple question: What is money?

This is a question that humans have asked themselves ever since they first bartered for goods and services. Does my bag of chickpeas equate in value to your axe-head – or at least, enough to convince you to trade?

About 5,000 years ago, the Mesopotamians created the shekel, which started out as a measure of weight and was co-opted to become the first known form of currency, being stamped with an official seal to certify its weight. Slowly the idea caught on to use these “coins” as a means of exchange and payment – especially when made of silver and gold, which helped establish these lumps of metal as stores of value, used to pay for exchanges of goods and services, and to pay armies. By the 7th century BCE, historians believe, the kingdom of Lydia (in present-day Turkey) — ruled at the time by a certain Croesus —began issuing the first regulated, standardised and certified coinage.

The idea appealed to the highly organised and bureaucratic Romans. Roman currency was widely used throughout western Eurasia and northern Africa from classical times into the Middle Ages. The Roman concepts of currency and the state holding the authority to mint that currency served as a model for the currencies of the Muslim caliphate and the European states during the Middle Ages and the Modern Era.

In other parts of the world, isolated from these advances, other peoples also faced the need to conduct transactions. Many used items from nature as natural tokens of value: on the shores of the Indian Ocean, cowrie shells became a currency in the trade networks of Africa, South Asian and East Asia. In the Pacific, the Fijians used whale teeth, and the people of Yap famously used huge carved disks of limestone, as currency. In the Americas, Native American peoples used tubular shell beads called “wampum” as money; the Mayans almost certainly used chocolate.

In its recognisable modern form, the Venetians codified credit in the 16th century, as a means of relying on people to borrow money and pay it back at a future date – the word “credit” comes from “credo,” Latin for “I believe.” The Venetians kicked the growth of money along massively with their honing of interest, being the amount paid to the lender, over and above the sum lent, or the principal.

Currency notes — on parchment or leather — appear to date from Carthage, and China, from around the same time, 150 BC—110 BC. The first known banknotes come from China in the 7th century, developed to allow merchants to carry their currency in lighter loads than piles of coins. The Mongols took this idea to Europe, where the first banknotes emerged in the 17th century. The Medicis charged commission on converting different currencies, inventing foreign exchange.

Come the 19th century, and the major trading nations – led by the British – had evolved an international monetary system based on the gold standard, in which the standard economic unit of account was based on a fixed quantity of gold. The nascent central banks — again. led by the Bank of England — agreed to exchange circulating paper and silver currency for gold bullion at a fixed price.

That worked just fine until the Great Depression blew it up, followed in short order by the Second World War. Realising that a new system was needed, the great powers convened the Bretton Woods Conference in 1945, from which emerged the fixing of world currencies to the US dollar, which was the only currency after World War II to be on the gold bullion standard. But these arrangements only lasted until 1971, when US President Richard Nixon took the US dollar off the gold standard, allowing for unconstrained increases in monetary supply (monetary inflation) causing the USA’s Consumer Price Inflation problem and to discourage foreign governments from redeeming more and more dollars for gold. The catalyst for the default might well have been the French warship arriving in New York to collect gold in exchange for French held US dollars.

Now, the world had arrived in the era of fiat currency, in which money was not backed by a commodity — or indeed, by anything — and could be simply created by a government and declared to be legal tender. Intrinsically, fiat money is valueless, with its “value” set by the market.

Central banks create this money and introduce it into the economy for which they are responsible, by buying financial assets or lending money to financial institutions. Commercial banks then “create” more of it by creating credit through fractional reserve banking, in which they deploy much more currency out in circulation than they possess — thus expanding the total money supply.

Any currency-issuing government cannot, in theory, run out of money. Its central bank can “print” money ad nauseam, increasing the amount of cash circulating in the economy — but risking inflation. More recently, central banks have opened up their toolkits to deploy “unconventional” monetary policy tools, such as quantitative easing (QE); in which a central bank purchases government bonds (or other financial assets) in order to inject monetary reserves into the economy, to stimulate economic activity.

Which they have done — and which some are now in the process of reversing, through “quantitative tightening” (QT).

In order to hold its value, we need to trust the government not to produce more of the currency, unfortunately governments seek election by promising just the opposite, debasing the currency and purchasing power via profligate fiscal spending i.e., monetary inflation which causes consumer price inflation.

Now, there is cryptocurrency.

Many people will not want to use digital currencies. Our ancestors did not necessarily want to accept a lump of metal for the cattle they were handing over, without getting another thing for it. Merchants did not necessarily want to accept a piece of paper instead of trusty coins. Promissory notes, credit, cheques, credit cards, EFTPOS, online banking — all of them would have looked very suspicious at first, and not only to the habitually cynical.

Bitcoin and the increasing digitisation of money is not going away. Indeed, the rise of Bitcoin and other decentralised cryptocurrencies has resulted in several central banks officially considering digital currencies as a more robust alternative to fiat currencies. As a result, most countries including China, the United Kingdom, the USA and India are all working on their central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which truly is a brave new world of digital money. CBDCs will be an improvement on the existing system, removing the archaic T+2 (transactions requiring 2 days to settle) but do present some surveillance and control issues for the public, China is ostensibly using its CBDC to control its citizen including an expiry date, use it or lose it currency!

Bitcoin further improves on CBDCs again, by returning to decentralisation model removing the ability for governments and banks to create money out of thin air, returning to a more stable gold standard model but with digital gold at its core which is much easier to move across counterparties, note gold typically costs 4% to freight and insure when changing hands. I wonder where the 3% figure for bank transactions came from!?

We believe such developments were inevitable once Bitcoin appeared —improvements on the current Fiat system include scarcity, verifiability (counterfeit proof), fungibility (no FX swaps) and more recently we have seen the importance of censorship resistance. This won’t happen overnight but do expect to see more CBDCs being launched this year, and more nations passing laws to make bitcoin legal tender.